The European Union’s groundbreaking AI Act, adopted yesterday by the European Parliament, marks a significant milestone in the regulation of artificial intelligence as it introduces a comprehensive framework to govern the development and use of AI while prioritizing the protection of fundamental rights. Particularly relevant to the creative industries is the Act’s approach to regulating the use of generative AI and addressing copyright concerns.

While some applications of AI may enhance creativity, generative AI often infringes upon authors’ rights by scraping copyrighted artworks for training purposes, leading to unfair competition and adverse effects on their working conditions. Generative AI can analyse and scrape data from existing creations and produce new ones on a large scale, capturing the essence of the training data without directly replicating it. This technology can generate a diverse array of content including images, videos, music, speech, text, software code, and product designs. Therefore, it has significant implications for cultural and creative industries.

For instance, in music, it can compose melodies, harmonies, and even entire pieces, offering musicians fresh inspiration and new directions. Similarly, in literature, generative AI can aid writers in brainstorming plots, characters, and dialogues, accelerating the storytelling process. Moreover, in film and video production, it can assist in generating visual effects, backgrounds, or even entire scenes, reducing production costs and time. However, its use also raises ethical and legal concerns within these industries. The unauthorized use of copyrighted materials for training AI models can lead to disputes over intellectual property rights. Additionally, there is a risk of devaluing original artistic works if generative AI floods the market with easily and fast produced content. Furthermore, there are questions regarding the authenticity and authorship of AI-generated creations, which may challenge traditional notions of artistic identity and integrity.

In summary, while generative AI holds great potential for enhancing creativity and innovation in cultural and creative industries, its implementation must be approached thoughtfully and ethically to mitigate potential negative consequences and ensure the protection of artists’ rights and originality. Members of the Parliament conducted several rounds of consultation with representatives of the CCS in the hopes of achieving this goal, secured by the transparency requirements. Now, the sectors look for inclusion in the discussions around the implementation process.

Let’s explore the specific provisions of the AI Act and their implications in detail:

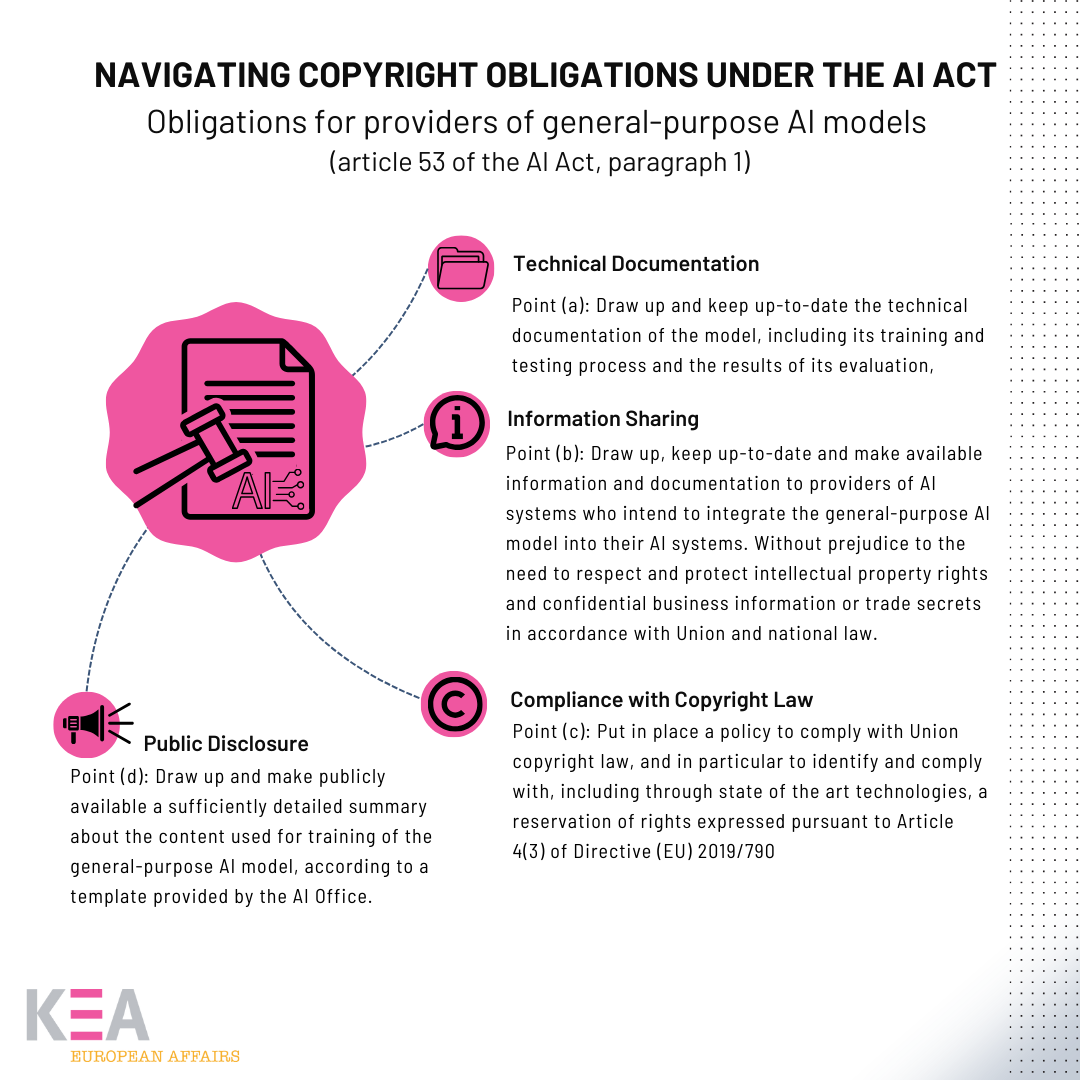

Transparency Requirements for General-Purpose AI (GPAI) Systems

One of the central aspects of the AI Act is the imposition of transparency requirements on providers. Recital 107 underscores the importance of transparency in ensuring accountability and facilitating the enforcement of copyrights. Specifically, it mandates GPAI providers to draw up and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used for training their models. This summary is expected to provide comprehensive information about the datasets used, including both public and private sources, to enable rightsholders to exercise their rights effectively.

The AI Office should develop a standardized template for summarizing training data, ensuring simplicity and effectiveness while allowing providers to present the required information in narrative form. And, in accordance with Recital 108, the AI Office should also monitor compliance with these obligations without conducting individual assessments of copyright compliance for each piece of training data.

The final text of the AI Act represents a significant advancement from the draft version, particularly addressing industry concerns regarding the ambiguity surrounding the process of the summary elaboration. In the original Parliament text, there was a notable lack of clarity regarding the distinction between copyright-protected and public domain training materials, leading to concerns about the practicality of applying different transparency standards to each. Now, the requirement for a summary is described as generally comprehensive in scope rather than technically detailed, making it more accessible for parties with legitimate interests, including copyright holders, to enforce their rights under Union law.

Additionally, the establishment of a “simple and effective” template for the summary by the newly created Commission’s AI Office further streamlines the process, addressing concerns that the original provision might burden model providers with excessive detail and effort. This clarification not only alleviates concerns raised by stakeholders but also ensures that rights holders have dedicated instruments to protect their interests.

Limited exceptions for text and data mining

The AI Act introduces limited exceptions for text and data mining, recognizing the importance of balancing copyright protection with promoting innovation and research. Recital 109 acknowledges the need for proportionality in compliance requirements, particularly for SMEs and startups. This provision aims to facilitate non-commercial research activities while ensuring that rightsholders’ interests are adequately protected.

Recital 105 underscores the importance of obtaining authorization from rightsholders for any use of copyrighted content in training AI models, unless relevant copyright exceptions and limitations apply. It highlights the provisions of Directive (EU) 2019/790, which introduced exceptions and limitations allowing reproductions and extractions of works for the purpose of text and data mining under certain conditions. However, it clarifies that rightsholders may choose to reserve their rights to prevent text and data mining (the ‘opt out’ option), unless it is for scientific research purposes.

Moreover, Recital 105 explicitly links the use of copyrighted works for AI model training to the text and data mining exception in Article 4 of the Copyright in the Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive. This linkage aims to put an end to disputes regarding the applicability of this exception to AI model training. It reaffirms that even if the legislator did not explicitly envision these uses when discussing the TDM exceptions, the AI Act recognizes that Article 4 of the CDSM Directive applies to such uses.

Jurisdiction and Compliance

Recital 106 of the AI Act emphasizes the imperative for providers of general-purpose AI models to ensure compliance with relevant regulations when placing their products on the Union market. This requirement entails establishing policies to adhere to Union copyright and related rights laws irrespective of where the copyright-relevant activities associated with the training of these AI models occur. As put in the legislation, “Any provider placing a general-purpose AI model on the Union market should comply with this obligation, regardless of the jurisdiction in which the copyright-relevant acts underpinning the training of those general-purpose AI models take place”. By mandating compliance with Union copyright standards, the regulation seeks to prevent any provider from gaining a competitive advantage by applying lower copyright standards. This ensures that all providers adhere to consistent copyright regulations, thereby promoting fair competition and safeguarding the interests of creators and rightsholders.

Moreover, the recital reflects the need for harmonized regulations across jurisdictions to address the evolving landscape of AI technologies and states a broader call for international convergence in the topic. With it, the EU reaffirms its commitment to global leadership in shaping the regulatory framework for AI technologies, demonstrating its determination to set standards that resonate worldwide.

Implications and future directions

In conclusion, while the AI Act represents a significant step forward in regulating the intersection of artificial intelligence and copyright law, its journey to becoming fully enforceable is not yet complete. The regulation is undergoing final scrutiny by lawyer-linguists and is expected to be formally adopted before the end of the legislative session through the corrigendum procedure. Additionally, formal endorsement by the Council is required.

Once published in the official Journal, the AI Act will enter into force twenty days thereafter. However, its full applicability will be phased in over a period of time. Bans on prohibited practices will take effect six months after the entry into force date, followed by codes of practice after nine months, and general-purpose AI rules including governance after twelve months. Obligations for high-risk systems will be applicable after a period of thirty-six months.

These staggered implementation timelines reflect the complexity of the regulation and the need for adequate preparation by stakeholders. As the AI Act moves towards full implementation, it is essential for all involved parties to understand and adhere to its provisions, ensuring a smooth transition towards a more regulated and responsible AI landscape.

As the EU moves towards the full implementation of the AI Act, stakeholders in the creative industries must collaborate to ensure effective enforcement and compliance with the legislation. This includes fostering international cooperation in copyright enforcement, developing standardized practices for compliance, and promoting dialogue between rightsholders, AI providers, and policymakers.

While the EU AI Act represents a crucial step towards responsible AI governance, it is essential to balance innovation with the protection of fundamental rights. Through continued engagement and collaboration, stakeholders can navigate the complexities of AI regulation while fostering a thriving creative ecosystem that respects rights and promotes innovation.

References

Texts adopted – Wednesday, 13 March 2024 (europa.eu)

Artificial intelligence act | Think Tank | European Parliament (europa.eu)

The Act Texts | EU Artificial Intelligence Act