This blog focuses on the representation of the Cultural and Creative Sectors’ (CCS) interests at EU policy level. It proposes a taxonomy of CCS policy networks active at EU level, highlights challenges in addressing policies relevant to the sector, and proposes ways to improve the level of CCS engagement in EU policies (research, green deal, competitiveness). It stems from the research carried out in the context of the EU- funded CICERONE project (2019-2023) www.cicerone_project.eu

Introduction

CCS representation matters. This can be illustrated in relation to a recent major EU policy initiative establishing a Knowledge Innovation Community (KIC) for culture and creativity. In October 2019 a new KIC focused on the culture and creative sector to financially support innovation and entrepreneurship over a 7-year period (renewable once) was announced. The winning consortium was selected in the course of 2022. EIT Culture & Creativity brings together 50 consortium partners from across Europe to manage the innovation program. Among the partnership only four represent the industrial dimension of the CCS in Europe (Philips Design, Ogilvy, Mediapro and the EBU). Can and should the EIT’s investment priorities be developed without more involvement from the industry? This question becomes essential if one believes KIC is about bringing together businesses, research centres and universities to address competitiveness and sustainability issues.

Another example comes from the important campaign “Cultural Deal for Europe”, which aims to mainstream cultural policy and shape the EU policy agenda inspired by the Green Deal. Culture Action Europe (CAE), European Cultural Foundation (ECF) and Europa Nostra, the largest non-industrial CCS networks are leading this initiative. The industrial side of the CCS is not involved in such an important political initiative. It is like organizing a forum on health policy without the participation of private hospitals, doctors, trade unions, and the pharmaceutical industry. Does this serve the objective of mainstreaming culture in broader policy objectives?

Apart the cultural heritage sector, CCS interests have yet to make significant use of EU research programmes (Horizon Europe) or EU regional policy funds, the most important funding streams of EU actions [1]. These financial instruments are geared toward developing SMEs, social entrepreneurship, or industrial competitiveness aligned with green, digital, and sustainability objectives.

The CCS is also recognized as one of the priority 14 industrial ecosystems deserving a policy to assert EU’s strategic sovereignty. Political intentions are there, the capacity of the CCS to benefit from the opportunities has to be developed.

It is commonly agreed that the CCS in the EU represent a sector of the economy valued at €477 billion (close to 4% of EU value added) with around 8 million jobs and 1.2 million enterprises, essentially SMEs.

However, who speaks for the CCS, one of the EU’s largest and most dynamic sectors (notably in video games, films, luxury and fashion, music and publishing, or cultural heritage)? How does the CCS participate in policymaking or benefit from EU policies? It is important to understand better the way the CCS are organized as policy networks to assess the capacity of the CCS to address challenges linked to the digital transition, sustainability, artificial intelligence, new working practices, consumption trends and access to finance.

The CCS representation at EU level

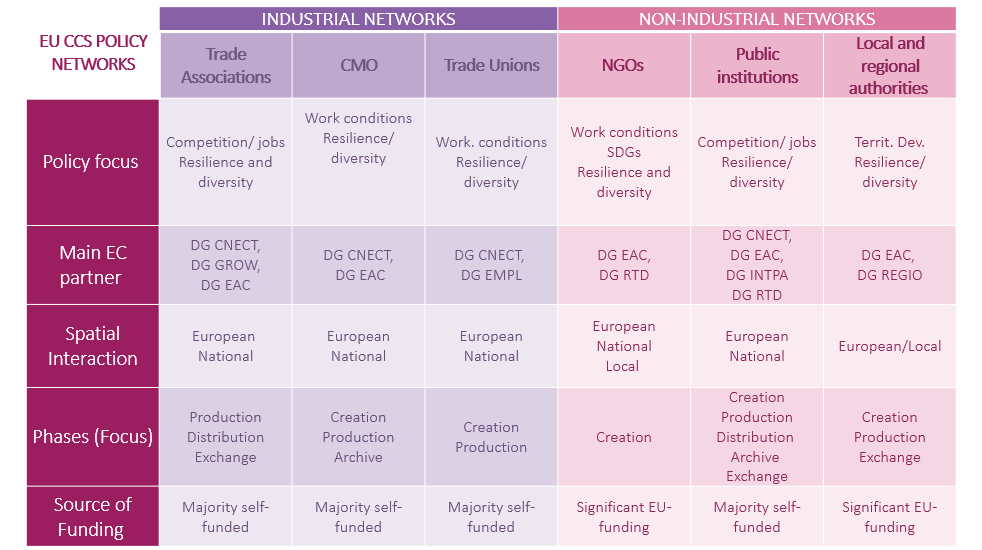

There are more than 110 CCS policy networks active at EU level. We propose the following classification of these networks:

Table 1: Types of CCS Policy Networks

Source: KEA (2023)

The types of CCS networks and their characteristics are detailed in the annex.

General observations on CCS representation at EU level

The mapping of CCS representation shows a wide variety of organizations working at different levels of policymaking, with different interlocutors and concerning various interests in the different phases of production networks. The deepest siloes found in the CCS representation are between industrial and non-industrial interests on one hand and between the stakeholders in the value chain: artists, creators, performers, producers, archiving and distributors on the other.

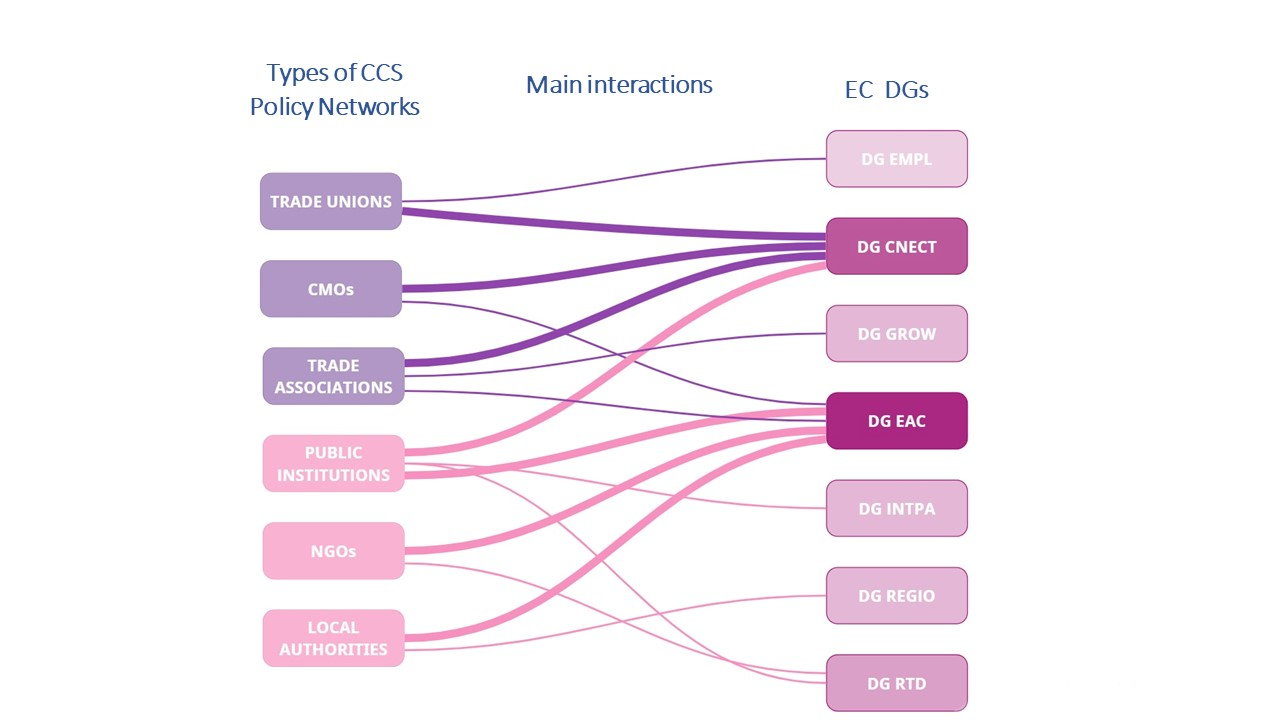

It should be highlighted that each CCS network has different interaction points with the EU institutional setup. The figure below shows the most common policy interactions between various CCS policy networks and EC arrangements. It reflects well on the need to streamline these interactions and develop a more coherent policy framework adapted to the specificities of CCS.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of main interactions between CCS policy networks and the European Commission DGs

Source: KEA (2023)

The siloed, incomplete, and spatially fragmented approach undermines the capacity of CCS to influence the policy agenda or benefit from EU programmes (increasingly open to CCS) and for policy-makers to apprehend the entire CCS ecosystem or engage with it. This largely contributes to preventing the building of a coherent EU policy for the whole CCS as an industrial ecosystem. CCS Subsectors have different policy interlocutors according to sectoral lobbying priorities, this undermines the capacity of CCS to be more effective as a collective and prevents the development of a coherent EU policy framework for CCS.

The effect of CCS representation on EU policies: a lack of coherence in policy actions

The impact of CCS representation is evident in the development of EU policies.

For instance, the Council’s Resolution on “the building of a European strategy for a cultural and creative industry ecosystem”[2] rightly highlights the importance of CCS for the green transition, social cohesion, regional development, and local regeneration. While addressing competition issues, it focuses on the power of global digital players and their position as “gatekeepers in the digital market.” It calls for:

- Better access to funding.

- Spurring skills development.

- Maintain the strategic autonomy of CCIS in the digital era.

However, it remains unclear how the CCS will be consulted to co-create a “transition pathway” similar to what is being developed for other ecosystems [3].

In parallel, the Council of Culture Ministers ‘Resolution on the EU Work Plan for Culture 2023-2026 [4], adopted on 28 November 2022, outlines different priorities for CCS, focusing on different policy networks with non-industrial objectives. The resolution identifies 4 priorities:

– artists and cultural professionals: empowering the cultural and creative sectors;

– culture for the people: enhancing cultural participation and the role of culture in society;

– culture for the planet: unleashing the power of culture; and

– culture for co-creative partnerships: strengthening the cultural dimension of the EU external relations.

These recent EU policy papers illustrate the different sets of policy priorities for the CCS, leading to different policy treatments and objectives addressing only part of the CCS, while excluding others. This perpetuates a siloed approach, which, exacerbated by substantial data gaps, undervalues the actual (economic, cultural, and social) values of the sector, thus questioning the focus and objectives of policymaking and, ultimately, its impact.

If we do not grasp the value of CCS and its way of operation, are we making the most of it? Is the support (whether financial or regulatory) missing critical bottlenecks?

Recommendations

The CCS share the following characteristics:

– Intrinsic motivation to work in the CCS, whether at the management or staff level considering the value and meanings of working for the arts and culture.

– The need to recognize the distinction between (economic) value capture vs (economic) value creation when assessing the importance of CCS.

– The capacity of CCS to foster social transformation, pluralism, freedom of expression, democracy, gender, cultural diversity, and increase the quality of life more generally.

– The importance of public support to encourage the setting up an environment conducive to the emergence of new talents, new creations, and production as well as educating audiences (notably through art education).

The GPN approach researched during the Cicerone project, reveals the hybrid relationships between for-profit and not-for-profit activities (thus showing an essential characteristic of CCS activities) not accounted for when valuing the impact of CCS. It highlights how CCS are actors of transformation able to achieve broader policy objectives such as sustainability, competitiveness, cultural diversity, and social inclusion goals.

Policy initiatives should create paths for increased collaboration between the industrial and non-industrial networks. They should embrace a cross-sectoral vision of the CCS and consider the perspectives given by the GPN approach when organizing consultations with the CCS to design policies. The setting up of a transnational CCS Alliance to cover the entire CCS production network and call for action on key policy priorities should be encouraged in line with successful national initiatives.

The CCS Alliance could be mandated to reflect on the following trans-sectorial policy topics for instance:

- Contribution to innovation and societal transformation to address the Green Deal and Sustainable Development Goals.

- Improve skills, training, and working conditions.

- Develop access to finance and consider the impact of financial models and rights acquisition which impact/threaten the economic value of cultural productions.

- Apprehend and influence technology development to the benefit of CCS and society.

- Contribute data to the CCS Observatory developed by Cicerone.

The CCS Alliance would also identify research topics for funding under Horizon Europe. Horizon Europe could support developing a CCS European Partnership. Ultimately the CCS Alliance would give concrete shape to the concept of the cultural and creative sector and enable the latter to be more effective in representing CCS’s collective interests.

KEA – 22.05.2023

Annex: Taxonomy of CCS policy networks.

There are two types of CCS policy networks: industrial and non-industrial CCS networks.

Industrial policy networks have as a main mandate to safeguard the economic interests of their members in the face of EU extensive regulatory powers that impact the functioning and development of culture and creative industries in the field of copyright, taxation (VAT), audiovisual media services, protection of minors, digital competition, or trade law.

Industrial policy networks play an important role in shaping the regulatory environment of the cultural sectorEU industrial networks gather:

- Trade organisations representing sectoral interests in the various industrial subsectors of the CCS (music, film, games, book publishing, broadcasting) – such as DOT Europe , IFPI, IMPALA, EBU, ACT, FEP, ISFE, CEIPI, EPC, EBU, Europeanvodcoalition, ACE etc.

- Collective rights management organisations (CMO) representing the interests of rights holders in the various subsectors where collective rights management structures operate (music (authors/composers, music publishers, performers and musicians) , film (performers, authors), visual arts such as GESAC, AEPO/ARTIS, SAA, EVA, etc.

- Trade Unions and organisations representing the interests of authors, artists, actors, musicians such as FIM/FIA/ ECSA /FERA, etc.

The main mandate of non-industrial CCS networks is to promote public interest objectives. The scope of activities includes Influencing the EU cultural agenda and work plan, promoting the mobility of cultural workers and artists and highlighting the importance of culture in the European project or the UN SDGs.

Three types of networks represent the non-industrial CCS networks:

- Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) gathering essentially not-for-profit cultural and social organisations (CAE, IETM, Europa Nostra, Trans-Europe Hall, etc.).

- National public agencies gathering governmental agencies in charge of managing aspects of the national cultural policy (national film agencies (EFAD), national culture promotion centers (EUNIC), etc.).

- Local authorities representing cities and regions looking at culture as part of local development activities (ERRIN, Eurocities, ENCC, a part of ECBN membership).

Resources:

[1] For the period 2021-2027 EU Horizon Europe that fund research and innovation has a budget of EUR 95 billion and the EU Cohesion Policy allocates EUR 392 billion.

[2] European Council. (2022). Council Conclusions on Building a European Strategy for the Cultural and Creative Industries Ecosystem (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7809-2022-INIT/xx/pdf)

[3] https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/transition-pathways_en – Tourism will benefit from such programme.

[4] Ibid. European Council (2022) Council Resolution on the EU Work Plan for Culture 2023-2026 (2022/C 466/01). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022G1207%2801%29